St. John’s to Labrador: A Dog’s Journey

You would never guess it based on its name but the story of the Labrador retriever starts on the cold, rocky coasts of Newfoundland. It’s the story of a fisherman’s dog who worked hard in the North Atlantic cod fishery helping people make a living in an unforgiving environment. It’s also the story of a dog driven from its home, only managing to survive because it won the heart of a handful of English aristocrats.

The Other Newfoundland Dog.

Alongside the famous Newfoundland dog, the island of Newfoundland was home to another, smaller breed of dog. It went by a number of names the St. John’s water dog, water dog, St. John’s dog and lesser Newfoundland. It was described as having a water repelling coat, webbed toes, and a strong rudder-like tail. It was the perfect companion and workmate for sea-faring people.

It’s been suggested that the St. John’s water dog arose from the pups of dogs European sailors brought to Newfoundland. It’s no stretch to imagine that the subsequent generations of Europe’s best sea-faring breeds might create a dog uniquely suited to coastal-living and maritime work.

And, it’s ability to work that cemented the St. John’s water dog’s place on the island. For early European settlers and seasonal fisherman, life in Newfoundland was tough and nearly lawless. It was true subsistence living. They couldn’t afford to feed a mouth that wasn’t going to contribute. The St. John’s water dog hauled nets and accompanied fishermen in their boats. One of the breeds chief duties was to leap from dories to retrieve cod the fisherman lost from their lines.

Along the way, some seasonal fisherman developed relationships with their water dogs and brought them back to England and Scotland.

St. John’s to Labrador, Via England.

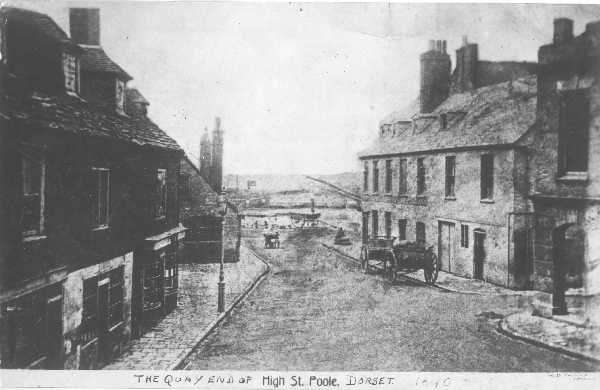

Poole, in southern England, was an important commercial centre in the Newfoundland fishery. Ships carrying Newfoundland cod routinely docked there. As sailors came into port they had their dogs swim ashore and demonstrate their retrieving skills. The English were impressed by the breed and soon there was enough interest to begin importing dogs for sale. Lots of people bought them including members of the aristocracy.

Poole High Street c. 1860. Image from Poole History Online.

The second Earl of Malmesbury lived just outside of Poole. He was an avid sportsman and realized the water dog would be the perfect duck hunting companion. It’s not clear when he got his first St. John’s water dog but there is evidence he was hunting with them by 1809.

St. John's Water Dog 'Nell' at 12 years old, 1867.

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Malmesbury kept a kennel of St. John’s water dogs and it’s a good thing he did because, for all the new interest in the breed, few people who bought them were able to continue the water dog bloodline. They began crossing them with other dogs and before long it was hard to find any ‘pure’ St. John’s water dogs in England.

Compounding matters, it was getting harder to get new water dogs from Newfoundland. Political changes reduced traffic between Newfoundland and Poole, tariffs were introduced on the selling of dogs, to stop rabies England instituted a lengthy quarantine on dogs and, most troubling, the breed was disappearing from Newfoundland.

Disappearance from the Island.

In 1780, the Governor of Newfoundland decreed that no family should have any more than one dog. The limit was set because the number of dogs in St. John’s had become “a very great nuisance and injury to the inhabitants”. This lead to a decrease in dogs in Newfoundland and, given that the island was home to unique breeds, a significant reduction in the population worldwide.

In 1815 there was a 5 shilling reward offered to anyone in St. John’s who destroyed any dog that was unmuzzled or at large. The lawmakers were concerned about ‘hydrophobia’ (rabies) in town.

The people of St. John’s were angry. An anonymous letter (see below) was fixed to the gate of the courthouse, addressed to the chief judge in the Supreme Court of St. John’s. It threatened an uprising should any action be taken against the dog, which many people in the city viewed as essential to their household. The judge promptly issued a £100 reward for information leading to the writer.

-

The following is the text of a letter fixed to the gate of the St. John’s courthouse in 1815 in protest of the proposed dog cull.

It was reproduced, supposedly verbatim, in Rev. Charles Pedley’s The History of Newfoundland.

—

To the Honorable Cesar Colcough, Esq., Chief Judge in the Supreme Court of St. John's, and in and over the Island of Newfoundland,

The humble petition of the distressd of St. John's in general most humbly sheweth: —

That the poor of St. John's are very much oppressed by different orders from the Court House, which they amigine is unknown to your Lordship, Concerning the killing and shooting their doggs, without the least sine of the being sick or mad. Wee do hope that your Lordship will check the Justices that was the means of this evil Proclamation against the Interest of the poor Families, that their dependance for their Winter's Fewel is on their Doggs, and likewise several single men that is bringing out Wood for the use of the Fishery, if in case this business is not put back it will be the means of an indeferent business as ever the killing Doges in Ireland was before the rebellion the first Instance will be given by killing Cows and Horses, and all other disorderly Vice that can be comprehened by the Art of Man.

Wee are sorry for giveing your Lordship any uneasines for directing any like business to your Honour, but Timely notice is better than use any voilance. What may be the cause of what we not wish to ment at present, by puting n stop to this great evil.

Wee hope that our Prayrs will be mains of obtaining Life Everlasting for your Lordship in the world to come.

Mercy wee will take, and Mercy wee will give.

—

You’ve got to love that salutation— supplication and threat rolled into one tidy package.

In 1885 the Newfoundland government passed a sheep protection act which placed a tax on dogs. There was a higher tax on female dogs, leading to people choosing not to raise female water dogs and, therefore, there were fewer litters of pups.

A fisherman with St. John's water dog in La Poile, NL. (1971)

Credit: Thewellman, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On top of that, the Newfoundland lifestyle and fishing practices were changing. The water dog, just wasn’t needed as it once was.

Through the 1900s, the species gradually disappeared in Newfoundland, at least as a distinct bloodline. Eventually the last of the island’s St. John’s water dogs died. It wasn’t as long ago as you might think. The last known dogs were a pair of males living in remote Grand Bruit on the island’s south coast.

They died in the 1980s.

Author Richard A. Wolters recounts his trip to Grand Bruit to see and photography these dogs in his book The Labrador Retriever: The History… The People (1981). The book contains some of the best images of the breed I’ve ever seen.

When the end of the line was in sight, there were attempts to save the breed in some form. One notable endeavour was undertaken by writer Farley Mowat in the 1970s. Mowat crossed his St. John’s water dog with a Labrador. Mowat went on to present Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau with two of these crosses.

Labrador retriever statue in Harbourside Park St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Securing the Breed.

If it weren’t for the English aristocracy, with their resources and keen interest in hunting, the breed would have been lost altogether. The Malmesbury kennel was maintained, and carried on by his son. They even managed to successfully procure a small number of dogs from Newfoundland to strengthen their breeding stock. Meanwhile, in Scotland the Duke of Buccleuch had started his own kennel of water dogs and also managed to obtain a new dog from Newfoundland.

Eventually dogs were exchanged between kennels and the breed was secured.

Enter the Labrador Retriever.

It is most likely these aristocrats were the men responsible for solidifying the name ‘Labrador’ for the breed. The first time the name appeared in print was in 1814 in the book Instructions to Young Sportsman. It appeared again in the title of an 1823 painting by Edwin Landseer.

In 1887 the third Earl of Malmesbury wrote a letter remarking on the name Labrador:

“We always called mine Labrador dogs, and I have kept the breed as pure as I could from the first I had from Poole (Harbour), at that time carrying on a brisk trade with Newfoundland.”

So why call them Labradors?

In the early days the breed was referred to by many different names, so for the sake of clarity, a single name had to be selected. The ‘retriever’ part was relatively straight-forward — they were always favoured for their fish and waterfowl retrieving. For a while the name English retriever was in use, but eventually the dog, or at least its name, came back home.

The name Newfoundland was, obviously, taken. Perhaps the Labrador’s geographic proximity to the island, coupled with the increased awareness brought about by English industry in the region the late 1700s, gave the name Labrador a boost in the mind of those early owners. It’s also been suggested the name Labrador came from the breed’s work retrieving in the Labrador sea.

In short, nobody really knows why ‘Labrador’ stuck. In any case, the breed received a name befitting its North American origin.

The St. John’s/Labrador Legacy.

The Labrador retriever may have started its life in the coastal communities of Newfoundland but it has taken the world by storm. According to the American Kennel Club it is their most popular breed of dog — and it has topped the list for the last 30 years.

My black Labrador Murphy proudly displaying his ‘throwback’ water dog white chest mark.

Through selective breeding the modern Labrador has changed from the St. John’s water dog.

Most St. John’s water dogs were black with white tuxedo markings. The modern lab has mostly, but not completely, lost its white. From time-to-time Labradors are born with white chest markings, the breed standards do not favour white so, in time, they may vanish completely.

The first recorded yellow lab was born in 1899 and chocolates were seen more frequently in the 1930s.

Tucker, my chocolate lab, as a puppy.

Regardless of colour, the key features of the water dog remain — a love of the sea, amazing drive to retrieve and, most importantly, a disposition pleasant enough to win the hearts of lawless seamen and refined aristocrats alike.

Hey, they’re not the most popular breed for nothing, you know.

The book The Labrador Retriever: The History… The People by Richard A. Wolters (1981) was a fascinating read and enormously helpful in pulling this together. The book seems a little hard to find these days (for a reasonable price, at least) but well worth reading if you get the opportunity.

Parting Shots

I’ve had the good fortune of sharing my life with four Labradors — Jake, Cooper, Murphy and Tucker. They all learned to tolerate my camera. Here are a few of my favourite pictures.